Image from NYtimes.com

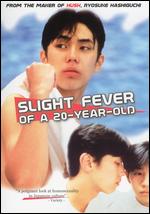

I find “queer” cinema’s imbalanced presentation of gays over lesbians a disturbing case of the pot calling the kettle black. As Pick notes, “While ‘queer’ ideally signals an emancipated (and potentially limitless) range of sexual and social relations, most of the products identified as ‘new’ and ‘queer’ were in contrast overwhelmingly male…does ‘queer’ stand for…the reintroduction of male hegemony, through the back door as it were?” (105). A transgressive medium that is supposed to provide progressive alternatives to limited mainstream thinking continues to perpetuate patriarchy by silencing women. Lesbians are practically invisible in the genre. Upon first glance, this seems the case in Slight Fever of a 20 Year Old (1993), a film that appears to focus exclusively on budding homosexuality in young male prostitutes. However, the objectified role of prostitutes reflects the commodification of women typical in male dominated countries. By seeing men mistreated in roles commonly doled out to women, we begin to see the horror synonymous with selling oneself. In the film, the girlfriends are not to be diminished; the unfulfilled crushes they experience are staples of the young lesbian experience.

A telling scene transpires between Tatsuru and a john. The customer, an older gentleman, asks the boy to massage his shoulders, an act traditionally designated to women of service. The man tells Tatsuru how he wishes he had a boy like him for a son rather than his daughter. The statement implies that if he had a son he would molest him, but that his daughter, given his homosexual bent, is useless. Denial of sexual vitality to women is crippling when their sensual prowess comprises their worth. The incestuous image is particularly creepy when one considers that many young women quietly suffer molestation at the hands of male relatives—including fathers. The john’s heterosexual façade feeds prostitution: The only institution in which he can explore his true nature while maintaining his accepted cover as straight husband and father. The myth of the nuclear family and normalized heterosexuality are inextricably linked for each lie needs the other to survive. Traditional marriage stifles female advancement in addition to that of homosexuals; straying from the ritual of “man and wife” means instant marginalization. For many, seedy professions like prostitution are the only options available once family and friends close doors.

Both boys—Tatsuru and Shin—have very flirty female friends who are spirited, outspoken, and arguably, quite strong. The girls’ craving for male attention is apparent; they actively pursue the boys who couldn’t care less about their cute fashion and long legs. The rejection and unsatisfied desire experienced by females in the film is a strong theme in lesbian stories. In a world in which women are defined by their relationship to men, women are encouraged to separate from one another; same-sex desire conflicts with the need to survive. Pleasure is traded for property—house, security, and respect (which depend entirely on an opposite sex partner). As a result, some young lesbians repress their passions. Even when they do confess, they are often turned down by the object of forbidden affection who realizes the danger inherent in girl-on-girl desire. Female frustration shown in the film’s straight females is, therefore, reminiscent of lesbian abjection.

Lesbians and gays share the oppression inflicted by the heteronormative machine; it’s time queer cinema shows both of their struggles directly by representing men AND women explicitly. Otherwise, injustice is advanced disguised as progressivism.

Pick, Anat. “New Queer Cinema and Lesbian Films.” New Queer Cinema: A Critical Reader. Ed. Michele Aaron. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers UP, 2004. 103-18. Print.

Slight Fever of a 20 Year Old. Dir. Ryosuke Hashiguchi. Perf. Yoshihiko Hakamada and Masashi Endo. Pia/Pony Canyon, 1993. DVD.